Before it was Butler, it was Fourth Lock

Posted On September 15, 2025

0

16 Views

Some towns are born on battlefield deeds. Others? A train whistle, a river lock, and a name that stuck harder than it should’ve.

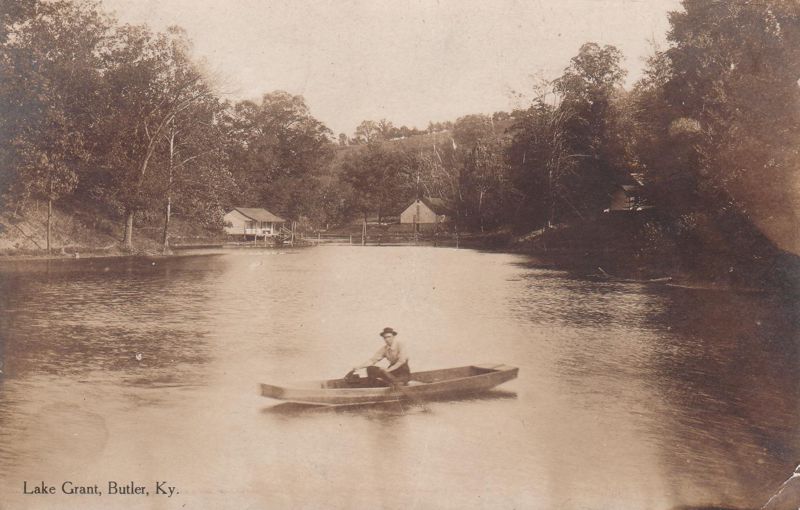

Before it was Butler, it was Fourth Lock, named for the ambitious but half-failed navigation system they tried to force onto the Licking River. That river, like the town, never flowed quite the way they planned.

Then the railroads came. In 1852, the Kentucky Central Railroad sliced through Pendleton County. Fourth Lock got a new name, briefly Clayton, until someone realized there was already a Clayton in Kentucky. So they swapped it out for a local legend.

William O. Butler, a soldier, statesman, Mexican War general. By 1868, it was official. Butler, KY stepped onto the map, forged by steel, water, and necessity.

Butler didn’t wait on incorporation papers to start moving. By the 1830s, the Ham brothers were already running stores. Mills were grinding. Trade was flowing, slow when the river was down, fast when the rails were live.

It was scrappy. The kind of place where you built something because no one else was coming to do it for you. The lock and dam dreams? They fizzled. The engineering was impressive, but the river was unforgiving, sometimes navigable, often not.

Butler was a functional waypoint for the region. Even before it had settled on its name. Positioned near the mouth of Crooked Creek, it served as a stopover for traders and livestock drivers working their way along the river routes and emerging rail paths. The land was fertile, and the early mills weren’t just grinding grain, they were anchoring the town’s role as a processing point for rural Pendleton County. Goods came in, feed and flour went out, and Butler quietly started serving communities that didn’t have the terrain or infrastructure to process their own harvests.

The town’s location also made it a strategic node during the Civil War. While not a battleground, its proximity to river and rail gave it logistical value. Union supply routes used the Kentucky Central line heavily, and Butler’s rail stop provided not only movement of goods, but a place for troops and materials to shuffle quietly through the hills. Though rarely mentioned in wartime dispatches, towns like Butler helped keep Kentucky’s contested middle from falling into chaos, by staying functional, steady, and ignored just enough to survive.

When the big plans died off, the people didn’t. They built schools, opened blacksmith shops, kept grain moving, and held the town together with nothing but mud, muscle, and maybe a little spite.

Today Butler is quiet. A few hundred people. Some old ghosts and a lot of cracked pavement.

The train doesn’t matter like it used to. The river’s just background noise now. But the names still hang in the air like humidity. Fourth Lock. Clayton. Butler.

They all mean something if you dig deep enough. What’s left is more than a town. It’s a reminder that even the incomplete, the replaced, and the shrinking still carry weight.

Whisper One Out

Trending Now

Pendleton County One Ambulance Away from Disaster

January 27, 2026

We Sent Our Kids to Be Safe And the System Ate Them

February 2, 2026